With the proliferation of wealth and social globalisation through media, the concept of motivation has developed into a core feature of popular discourse. This certainly has led to the concept being very prominent in the context of individual people’s lives and their self-fulfillment. In essence, motivation formerly described a goal-driven attitude towards taking action. Today, the concept is used more and more to describe the degree of energy utilised in executing certain actions, which can also be quite small and transactional. However, this concept is not fit to describe, and even less so to explain, development at the aggregate societal level. It cannot be denied that some regions and civilisations have had more extensive and intensive periods of development compared to other regions. Although every civilisation has had phases of accelerated development, there are some civilisations that, in the aggregate, developed more or longer. Without understanding the reasons for this imbalance, the simple mind quickly tends to associate some sort of superiority with those developing-prone civilisations over those civilisations with lesser development output. When measured by output, there is a fair argument that more productive nations and societies have added more to mankind than others. However, this does not imply a genetic superiority at the mental level, or even a variance in the human nature. Coming back to the concept of motivation, we could very simplistically say that those productive nations were, or are, more “motivated”. Motivation at the overarching societal level is to be viewed as the interplay of structural factors that force and incentivise certain behavioural patterns that are generally executed quite consistently throughout that respective society.

Environment and Survival

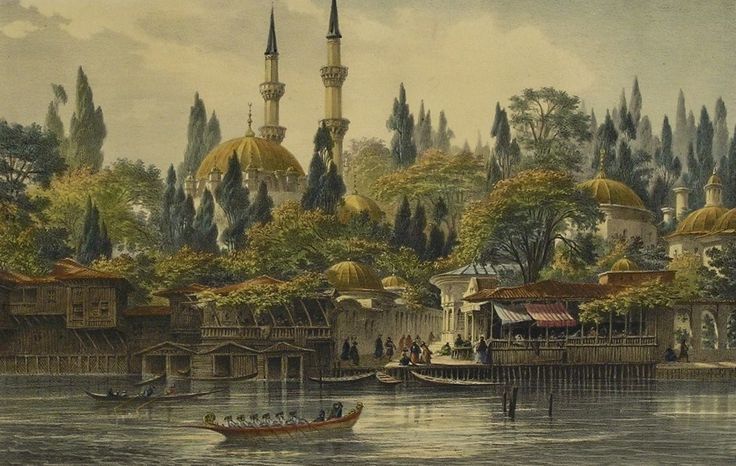

The first motivational factor, or driver, that influences our propensity to develop is the environment. Every living organism is limited to the laws of nature. Nature dictates the general course of things, and this is not only confined to the natural phenomena on this planet. Rain, wind, mountains, rivers, forests, day and night may be the most visible and tangible facets of nature that we interact with but also gravity, waves, magnetic fields, spacetime and dark matter are part of nature and its laws. As those things are in constant motion, there is a permanent necessity for organisms to adapt to those changes in nature. Whether we think about hurricanes, droughts, ice ages, floods or any other change in natural circumstances, organisms must adapt to them. Those organisms that can do so will survive. They may not do so in their initial form, but they will survive. As survival is the precondition for anything that lies beyond that, such as fulfilling our purpose in life by engaging in genuine knowledge production, adaptation is an essential mode of our being. On a more complex level, societies also need to adapt to those changes in nature, and we call this adaption process development. Societies are, in their specific form, born out of the unique properties of their home territory, as described in “Devlet” in great detail. Whether a people lives at the seashore, in the mountains or in the forest, whether the climate is warm, cold, humid, arid or windy, all affect how they try to survive. This dictates what capabilities they develop. At the sea, people will likely be good swimmers, and mountain people will be good climbers. The properties of the territory affect how food and water are obtained, which is essential for survival. It also determines how easy or difficult survival is, an important factor in our human nature. If there are many nutritious resources, survival becomes easier. And if survival is easy, there is less need for development. A people’s rate of development is influenced to a significant degree by the difficulty of survival. If the procurement of resources for survival is easy and there are no natural enemies or competitors for those resources, there is little to no need to further develop. Interestingly, this is not only applicable to nations with lower development rates but also to those nations that reached such a high standard of living that the necessity to develop is also declining; this is called decadency.

If there are, on the other hand, too many hurdles to survival, then development is also slowing down. When societies need to fully concentrate all of their powers primarily on obtaining resources for survival, then there is neither time nor energy to develop. For instance, people living in arctic regions are, due to the natural circumstances, so occupied with surviving that societal development is relatively slow. Also, civilisations that encounter massive competition due to scarce resources within a certain territory face developmental issues. Early Central European tribes, even though related to one another, were in a constant mode of fighting over scarce hunting and gathering grounds. It follows that neither easy nor hard modes of survival aid societal development. In the former case, there is a massive lack of “societal motivation” due to little incentives, while in the latter case, it is caused by a lack of power and time. This is not to say that those civilisations cannot overcome those issues. They will have to identify on which side of the spectrum they are and how they can utilise their unique territorial properties to their advantage. However, the phenomena explained above also illustrate why some civilisations had it considerably easier than others in terms of development. Their mode of survival was neither too easy to take away the “societal motivation” nor too hard to hinder progress. The mix of the parameters varied, of course. For one nation, there were abundant resources, but many enemies competed for them, so the balance between those factors led them to innovate certain technologies to fend off attackers. Other nations had less intervention from the outside but also fewer resources and, therefore, needed to develop new techniques to overcome those problems. Within this delicate balance, there is enough pressure to innovate out of necessity but also enough energy left to innovate out of habituation and passion.

Societal Factors

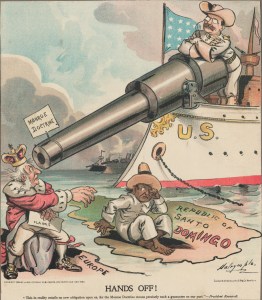

Although physical and structural factors are surely the main factors that determine a society’s development rate, it would be false to limit the analysis to only those factors. In the end, our mental capacities and pooled cognitive resources are to be seen as creative assets that can be used to mitigate the effects of low development and amplify the effects of advanced development. Here, the main component is the definition of a goal. With any action there is, the properties of the goal determine the properties of actions taken to reach them. The better societal goals are defined, the better societal development will be. Since the overall development stage of civilisations is still quite low in absolute terms, we can observe that even societal goals are still somewhat informed by survival considerations. We can see this when we look at the two main goals that have been reinforced politically over many centuries: power and wealth. Those relational goals, that are not inherently part of the human nature, require the existence of external actors to measure our success against, and the structural reason for that is that we still consider others as dangers to our survival. This can be in direct relationships, like in the economy, where companies want to become more powerful than others to hinder their competitors from taking customers away. However, the same holds true for individual societal conduct. Even when someone is very rich and can afford to access many more means of recreation and reproduction, those people will try to keep the competitive advantages over others to preserve the distance in status and recognition within society. A leveled landscape of wealth would imply the danger of social meaninglessness, the survival as a person of higher social value. This is all driven by the acceptance of power and wealth as meaningful goals. Actions taken in this direction are more outward-looking as they will always imply behaviours that are also directed towards the disadvantage of others. In the end, the power and wealth of one own is measured against the lack of power and wealth of others. Societal development suffers from this because even when innovation and progress rates are high, they will imply components that are directed towards the underdevelopment of other individuals or even societies.

Within the devletist school, those goals are seen as factors of lower value. It is more the full concentration on genuine knowledge production that will bring a society closer to its true development potential. This goal formulates an aim that each civilisation can reach by its own unique means without entering into conflict with other civilisations. The “societal motivation” then stems from an inherent curiosity about the true nature of being. By enabling its population to strive for this understanding of being, devletism is the politically materialised form of societal development. Here, there will be high rates of social progress coupled with the development of structures to overcome the physical and structural development hurdles explained above. It is a significantly more difficult approach but with a guaranteed outcome, namely lasting societal development. As long as civilisations do not switch to the devletist mode of governance, all the factors explained above will remain in a constant circle of ups and downs in the development rates of civilisations. Even high rates of developmental success will ultimately result in decadency, restarting the circle once again. Devletism overcomes those circles and moderates the ups and downs in societal development. It might be harder to build the system and keep it intact with constant work, but the downside risk of lethargy is reduced to a minimum. The best thing about it is that devletism is not in conflict with human nature – the opposite is the case. Since it draws on the inherent differences that stem from environmental factors, it incorporates human nature and channels it to be productive.